The power of the map is undeniable. The map serves as common ground in my classroom: no matter your discipline, there is little debate about the equity a map has in communicating patterns and processes at varied scales. Sure, it doesn’t hurt to be a geographer to have this perspective, but it is by no means a prerequisite. The OSM Community facilitates the improvement of the human condition through the collective power of the map.

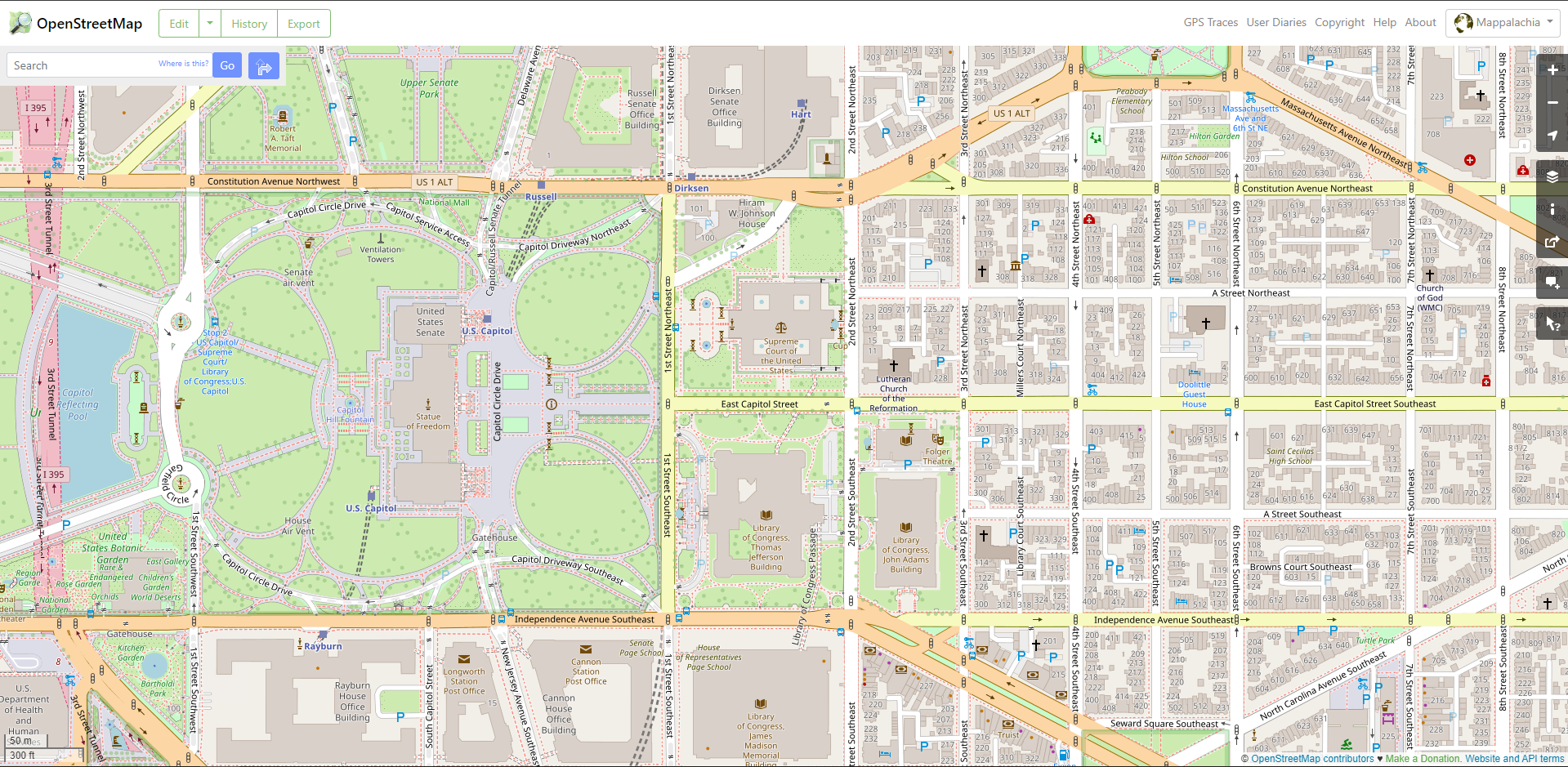

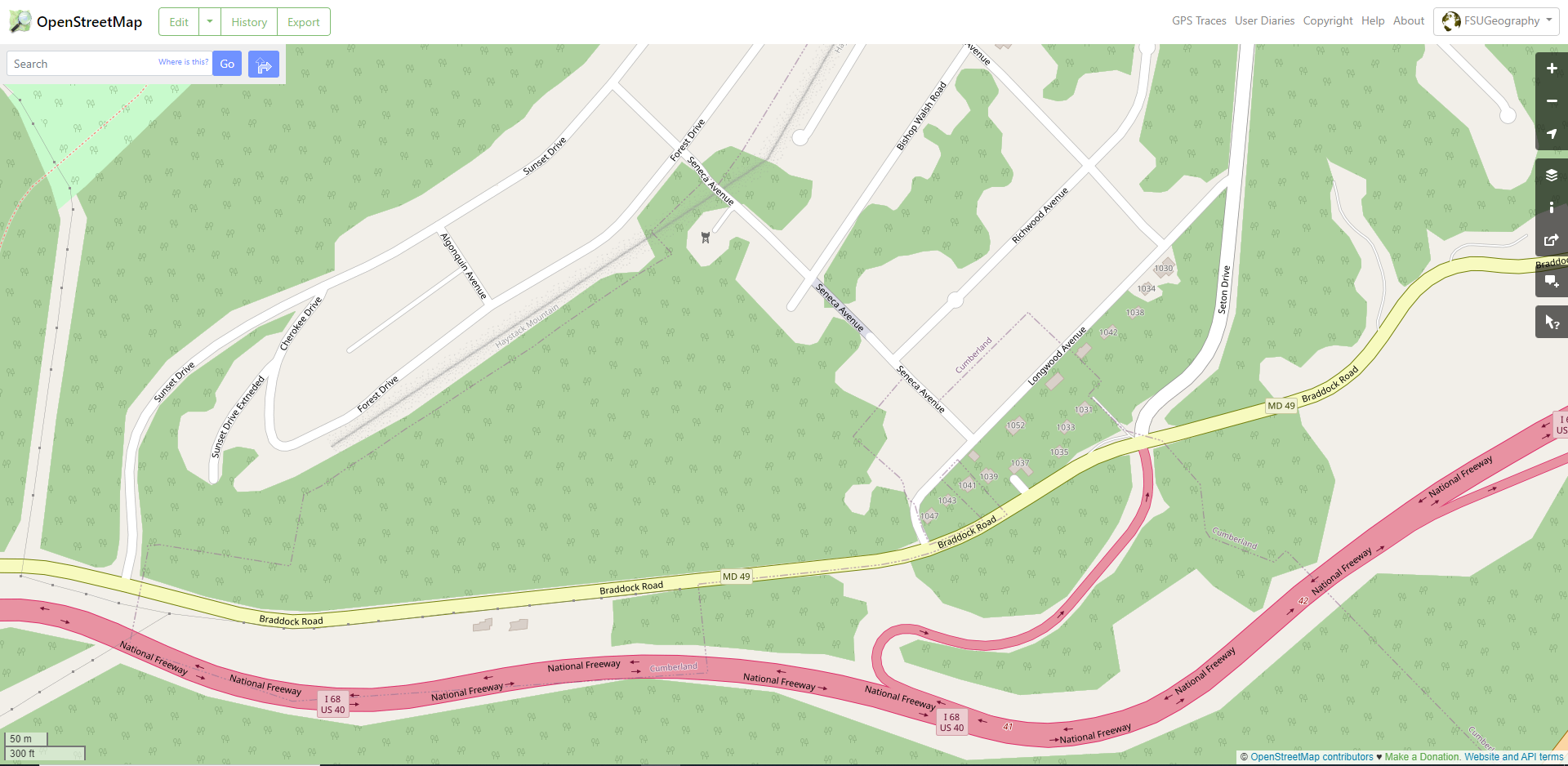

My relationship with OpenStreetMap is five years old, and I have turned a corner from a beginner mapper to intermediate. The pandemic’s push to online for my courses was the nudge necessary to transition from wiggling my toe in the OSM ecosystem to taking a deep breath and diving in. During this time, I have increased student exposure to OSM at Frostburg State University: formal lab exercises in my cartography courses, highlighting humanitarian mapping efforts in my introductory courses, evening Map-a-Thons open to anyone on campus, and most recently, a shared mapping task with Dr. Tom Mueller and his students at Pennsylvania Western University. While learning OSM, I have been looking for my niche, and I have come out on the other side with a rallying cry: Map Appalachia! Many portions of the United States are mapped with incredible detail in OSM, but swaths of Appalachia are underrepresented or terra incognita altogether. Consider the detail of Capitol Hill compared to my region of rural Maryland only two hours to the northwest in the mountains of Appalachia.

When the OSM Community discusses missing portions of the map, the conversation often orbits developing parts of the world, and for good reason. However, similar gaps can be identified in highly developed nations, too. Appalachia serves as a touchstone in that respect, as do the Great Plains. The recurring question in mapping Appalachia has been “where to start?” Primary transportation arteries offer a springboard to collaborative mapping in underrepresented regions. These routes often contain much of the population in clustered rural settlements, they provide a logical progression to lower-order streets that feed into them, and most importantly, they are connections between regional mappers.

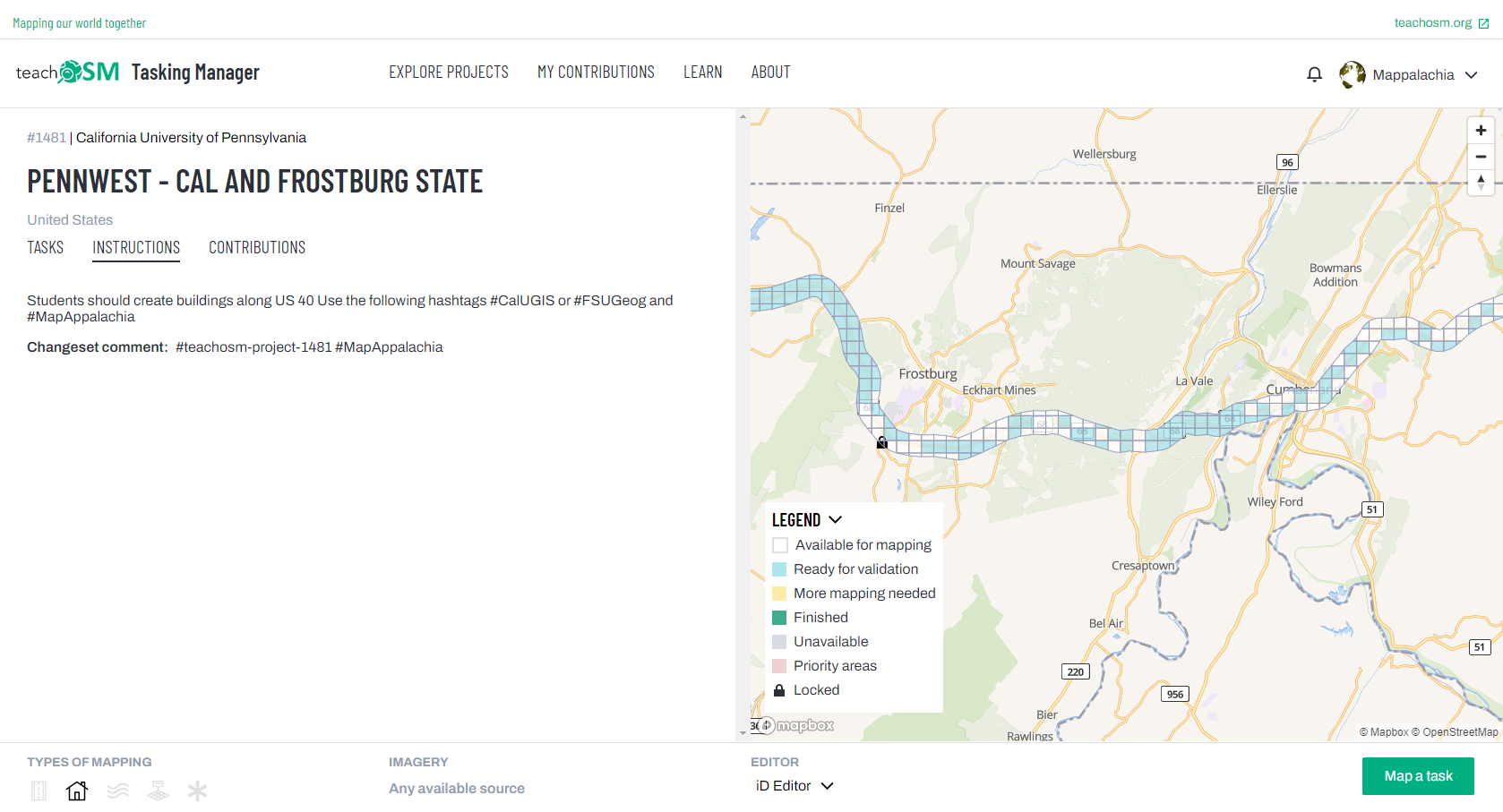

In the second half of the Fall 2022 Semester, Tom Mueller’s online Geobusiness course at PennWest and my on-campus Cartography course at Frostburg utilized the seventy miles of US-40 separating our institutions to begin filling in the map between us. Our initial focus was buildings. To keep everyone organized and along the chosen route, Tom crafted a task in the TeachOSM Tasking Manager (which you can learn to do here: https://teachosm.org/projects/2020-03-10-824075) and utilized a US-40 shapefile to create the area where contributions would be requested. The shapefile was clipped to only incorporate the counties between the universities through which the route passed, and a 0.25mi buffer was placed around the road. From there, all that was left was for students to map through varied guided course assignments on our respective ends, with the Tasking Manager providing an ideal conduit.

Formal classroom mapping was complimented by Geography Awareness Week, which falls on the third week of November each year. Frostburg’s germinating GTU YouthMappers chapter hosted a Map-a-Thon during GIS Day that was open to the campus community and focused on the task.

Turnout on GIS Day was encouraging! Campus members with no exposure to OpenStreetMap came with laptops, and those that didn’t have a computer were set up in an adjoining lab. I gave a short discussion over pizza on participatory mapping and the principles of OSM along with demonstrating how to provide good edits before everyone started. During the mapping, I mostly floated between rooms to check on progress, offer guidance and encouragement, and maybe snag an additional slice of pizza.

In retrospect, this TeachOSM pilot demonstrates ample potential for collaboration between two groups in regional proximity. Living in an under-mapped area is certainly a challenge, but it is also an opportunity when other groups in the region have similar aspirations for enumeration. Working towards each other along the transportation corridors that connect us utilizes local knowledge, often focuses effort in areas with relatively higher population densities, encourages communication between vested interests where it may have been absent, and ultimately, speaks to that latent power resting in the collective. Admittedly, it was disappointing to not have both groups come together at the end of the semester for lunch and a debrief, and there were a few challenges along the way such as minor vandalism and the 0.25mi buffer not catching some residential areas, but the activity was no doubt successful in addressing underrepresentation.

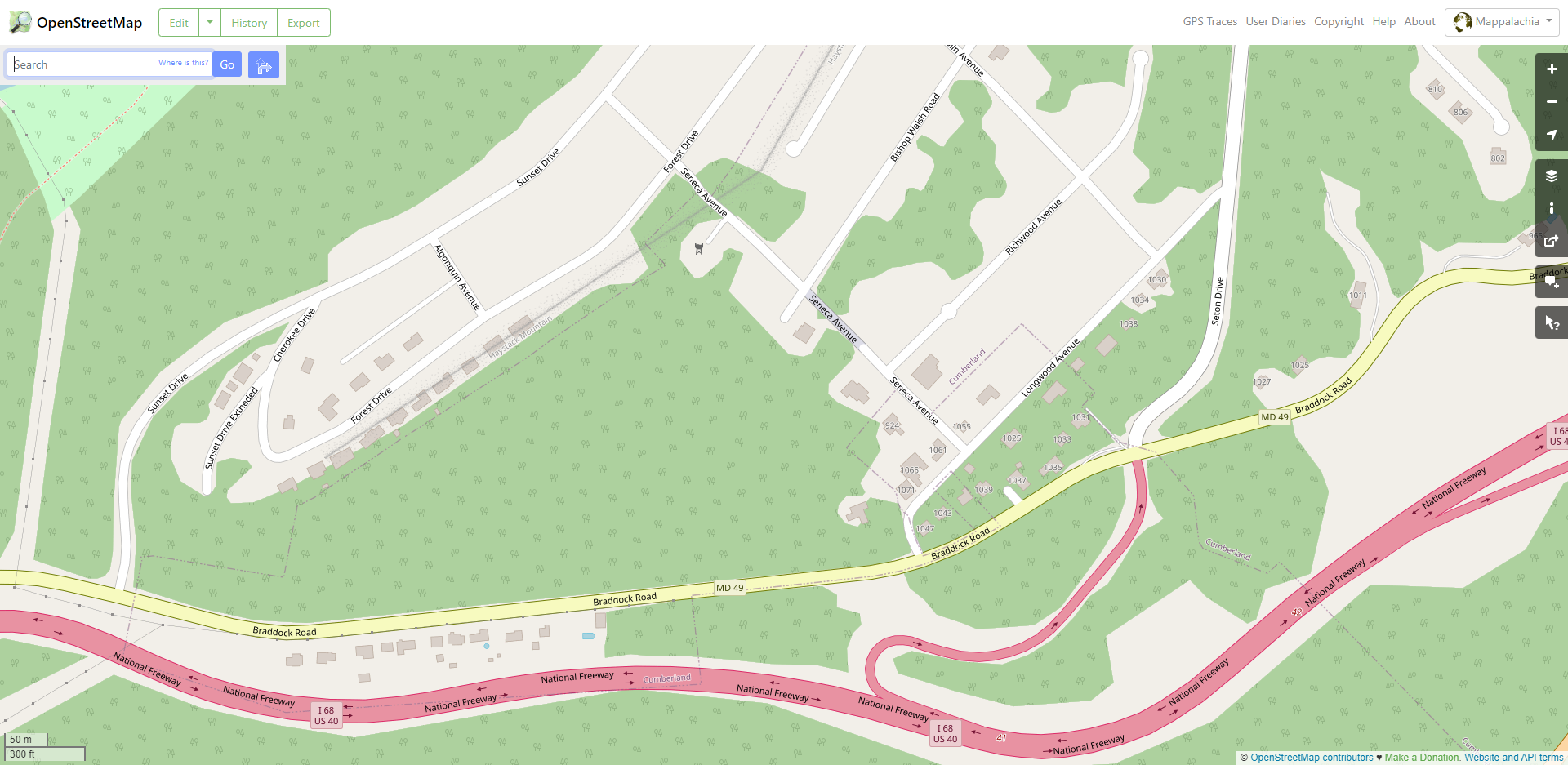

Students from Pennsylvania Western University and Frostburg State University provided over 1,200 changesets that contributed over 6,000 new map edits to OSM. Recall the difference in detail between DC’s Capitol Hill and LaVale, MD provided in the beginning; below is that same area after being mapped. While there has been clear improvement, you can plainly see the 0.25mi buffer straddling US-40 and the neighborhood that fell outside of the Tasking Manager.

In other areas, such as where US-40 passes through Brownsville, PA a few miles south of PennWest, the buffer was more efficient in capturing missing areas. This is because the route better approximates the historic National Road through Brownsville but follows the more modern interstate system closer to Frostburg. (Please note that the Brownsville before/after example below is displayed at a slightly smaller map scale than the previous figures.)

The limitations encountered in no way detract from the utility of this methodology. The empty spaces betwixt groups are not going to be mapped completely in one fell swoop. If you’re interested in tackling your underrepresented corner of OSM, it’s likely you are not alone. Begin by seeking partnerships within an approachable geographic radius, engage in dialogue to formulate a plan, set your parameters, and don’t be afraid to ask questions or make mistakes as you start down the road, literally or metaphorically.

Finally, Tom and I would like to extend our sincere gratitude to the TeachOSM Community for helping facilitate the success of this pilot study with the awarding of a collaboration grant. Furthermore, Steven and Jess remained supportive throughout our work, and their feedback was most appreciated. Here’s to many more mappy adventures.